Most people know that it’s important to have underground utilities located before construction or excavation projects. Damaging utilities can be costly and dangerous. What many people don’t know is that construction can also severely damage tree roots, weakening a tree’s health and stability. Root damage from construction is one of the leading causes of tree decline and death in urban areas. Very often trees are damaged in the construction of new homes or outbuildings, and then later become hazards to those same buildings. To understand why this is, and why you might want to call an arborist before you dig, we need to first examine what tree roots look like below the surface.

What do tree roots actually look like?

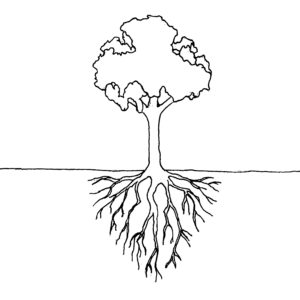

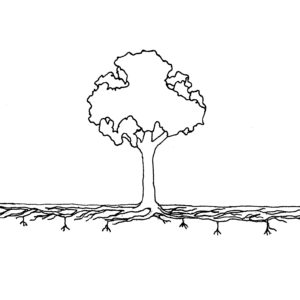

Do a google image search for “drawing of tree roots” and you’ll end up with hundreds of images like Figure 1. This hourglass shape is how most people imagine a tree’s roots, but it is largely inaccurate. Figure 2 is a more correct depiction of how tree roots actually look underground. A common misconception about trees is that their roots grow downward, and that the shape of the roots mimics the shape of the crown. In reality, tree roots spread horizontally just below the surface. They can spread for considerable distances, and they often aren’t symmetrical. As roots spread they create what’s known as the root plate. The width of the root plate of a broadleaf tree can be three times the width of its drip line. Picture a maple growing in the center of an open lawn. Let’s imagine that the crown is ten feet in width. Walk outward from the trunk to the drip line and you’ll be standing on roots. Walk another five feet and you’ll probably still be standing on roots. Walk five more feet and you might still be standing on roots. And you’ll be literally right on top of them. That’s because most of the fine absorbing roots, which take up water and nutrients, are located in the top 6-12 inches of soil. Roots are rarely encountered below a depth of three feet.

We find absorbing roots mostly in the top layers of soil because that’s where all the action is. Soil is a living ecosystem that trees depend on. Coarse organic matter accumulates on the surface and gets incorporated into the top soil horizons. There it gets broken down, consumed, and cycled by a whole network of soil organisms. These range from earthworms to mycorrhizal fungi to microscopic nematodes. Roots and soil organisms both require oxygen and good drainage, conditions that occur closer to the surface. The upper layers of soil are the most biologically active, so this is where we find tree roots making their living.

Another common misconception is that large trees have long taproots holding them in place. Taproots are usually only a feature of very young trees, and few mature trees have them. A seedling sends down a taproot in order to quickly access nutrients and water, increasing its chances of survival. As the tree becomes established, taproot growth ceases and lateral roots begin to form. As the name implies, lateral roots spread horizontally. They taper rapidly near the trunk and branch into long, rope-like structures just below the surface. The fine absorbing roots then form on the surface of these larger roots. It is these lateral roots, not taproots, that anchor the tree.

It’s important to note that root systems develop in response to environmental conditions. The shape of root systems will vary with species, soil, and climate. An oblique root is a type of root that spreads downward at an angle between vertical and horizontal. Oblique roots are more common in species native to arid regions. In those areas trees might form root balls more than root plates. However, in temperate regions like the pacific northwest, lateral root systems predominate. Watering regimes influence how deep rooted or surface rooted a tree becomes. Poor soil conditions can cause roots to spread farther than those growing in fertile soils. In urban areas where soils are greatly altered, infrastructure and compaction will influence how roots develop. All of this makes it challenging to determine exactly where roots have formed, but we can make some generalizations. Simply put, tree roots grow where conditions are suitable for growth. Those conditions are usually close to the surface, and growth is not restricted to the area of the drip line.

Construction can cause root damage in several ways

Compaction from heavy machinery and vehicle traffic will kill roots. Raising the grade, or mounding soil and gravel in the root-zone, can smoother roots. Altering a site’s drainage; changing how and where water flows, can have adverse affects. Roots are encountered above the depths required for buried utilities, and trenching close to trees will sever major roots. Cutting a single major root near the trunk can result in the loss of 25% of the root mass. How much a tree can withstand loosing depends on several factors. Certain species are capable of withstanding more root loss than others. Older, mature trees are less able to cope with severe disturbances than younger trees. A tree that is already stressed, by bad pruning or severe drought for example, will be further stressed by root loss. Root damage not only affects the health of the tree, it also compromises stability. A major function of the root plate is to keep the tree securely anchored. A tree with damaged roots will become more prone to falling over. Severing a root also creates a permanent wound which becomes a gateway for pathogens and wood-decaying fungi. These can spread into the trunk, further weakening the tree’s structure.

Often the affects of root damage aren’t immediate and can take several seasons to appear. In other cases trees will begin to decline very quickly. Figure 3 shows a pine tree in Sequim that suffered root damage from construction and died the following year. This pine was vibrant and healthy prior to installation of the concrete slab and gravel parking area. These areas were previously open landscape beds that the tree roots had colonized. Root damage occurred across the entire area from grade changes, machinery and vehicle compaction, excavation to remove the existing landscaping, and trenching for a water line (note how close the valve box in the center of the photo is to the pine). Figure 4 shows the dying pine a year later. It has since been removed. Unfortunately, the root zone of the Deador cedar was also impacted by the construction. It might also begin to show signs of decline at some point in the future.

When to call an arborist

It’s important to call an arborist in the early planning phases of a construction project. Builders are usually not trained in the biology and management of trees. Often they are unaware of the damage that construction can cause and how to prevent it. Calling an arborist can help you avoid loosing valuable trees, and save you from high removal costs down the road.

At Arbor’s Edge, we first determine which trees are the best candidates for preservation. We take into account tree species, health, age, and structure. We assess the spread and form of roots. We consider how construction will alter growing conditions. We determine how selectively removing trees will impact those remaining. A tree protection zone, or TPZ, is established around trees that will be preserved. The TPZ is a cordoned area that becomes off limits to all construction activities. The size of the TPZ is determined by the amount of root mass that needs to be protected. In areas outside the TPZ, compaction can be mitigated by spreading thick, temporary layers of mulch. Where utilities need to be installed, they can be tunneled underneath roots to avoid cutting them.

It isn’t always possible, or desirable, to preserve every tree, especially on large projects. Sometimes building plans can’t be altered to accommodate tree roots, and those trees must be removed before construction begins. As mentioned, trees are often damaged during construction and then become hazards to new buildings and structures. Removing a tree close to a structure, especially one that is dying or unstable, is more expensive than removing the same tree from an open area.

Severe tree decline is usually not reversible. Preventing problems before they occur is crucial when it comes to trees, because there aren’t many easy cures. With a little planning and foresight, you can continue to enjoy the benefits of your trees for years to come.

Call Arbor’s Edge today to schedule a consultation.

References

Harris R.W., Clark J.R., & Matheny N.P. (2004). Arboriculture: Integrated Management of Landscape Trees, Shrubs, and Vines. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.